Have you ever had one of those weeks in which the inspiration just isn’t there? Over the past several days, I’ve written the first few hundred words to three separate articles. The problem is that I was not enjoying what I was writing in the slightest, and I’m a strong believer that if the writer isn’t enjoying the work, then the reader certainly won’t either. I’m sure one day I’ll revisit these posts. I like the concepts, I just couldn’t manage to make the words interesting, or entertaining, or effective. Something I’m sure we all fear when we start a project.

So I was sitting on my couch, devouring pizza and bingeing buddy cop procedurals, bummed because I had nothing to say to you this week. But then the winners of the 2023 Pulitzers were announced. In the criticism category, the award was given to Andrea Long Chu for a handful of pieces she’d written over the last year. She’s one of the most well-deserved winners in recent memory. One of the pieces she was recognized for, “The Hanya Yanagihara” principle, is an expertly written criticism of that author’s goliath of a bestseller — and book community darling — A Little Life.

The rise of stan culture and social media has helped to brutalize the art of criticism. And it is an art. Just like an exceptional novel, memoir, film, or album, criticism broadens our understanding of the world in which we’re living as it gives a voice to those who find themselves trying to put into words their emotion or reaction to a work of art. It helps us get to know the subject matter and ourselves better. Even when you disagree with a critic’s assessment, they give you a new perspective with which to examine something you adore.

While artists reacting negatively to criticism is hardly a new phenomenon, it’s been magnified by social media and the rise of “stan Twitter.” These are online communities comprised of an artist’s most fervent followers. They’ll attack anyone seen to be criticizing their star. Groups like the swifties (Taylor Swift), the BTS army (k-pop group, BTS), and the beyhive (Beyoncé) have all been the source of vitriolic comments, racist tirades, and death threats towards individuals who they believe slighted their chosen artist. The artists themselves do a poor job navigating these communities, often letting fly their own attacks at critics who have cast them in a negative light. Swifties, after the singer called out a Netflix show for making a comment about her love life, swarmed everyone involved with the production.

Other artists have personally attacked music critics after receiving a negative score on an album. Lizzo tweeted, “PEOPLE WHO ‘REVIEW’ ALBUMS AND DON’T MAKE MUSIC THEMSELVES SHOULD BE UNEMPLOYED,” in response to a Pitchfork review giving her album a 6.5. After a negative review of her album Manic from the same outlet, Halsey tweeted, “Can the basement they run p*tchfork out of just collapse already.” Her followers were quick to point out that the publication was in fact run out of the World Trade Center and Halsey had unintentionally made an allusion to 9/11. The tweet was deleted.

The biggest independent music critic on the internet, Anthony Fantano of The Needle Drop on YouTube also gets an inordinate amount of hate. His most famous video is his 2010 review of Kanye’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy which he scored a 6/10 (a generous score, in my opinion). To this day, he still gets attacked online about that review and you can see people referencing it under almost every one of his tweets more than a decade later.

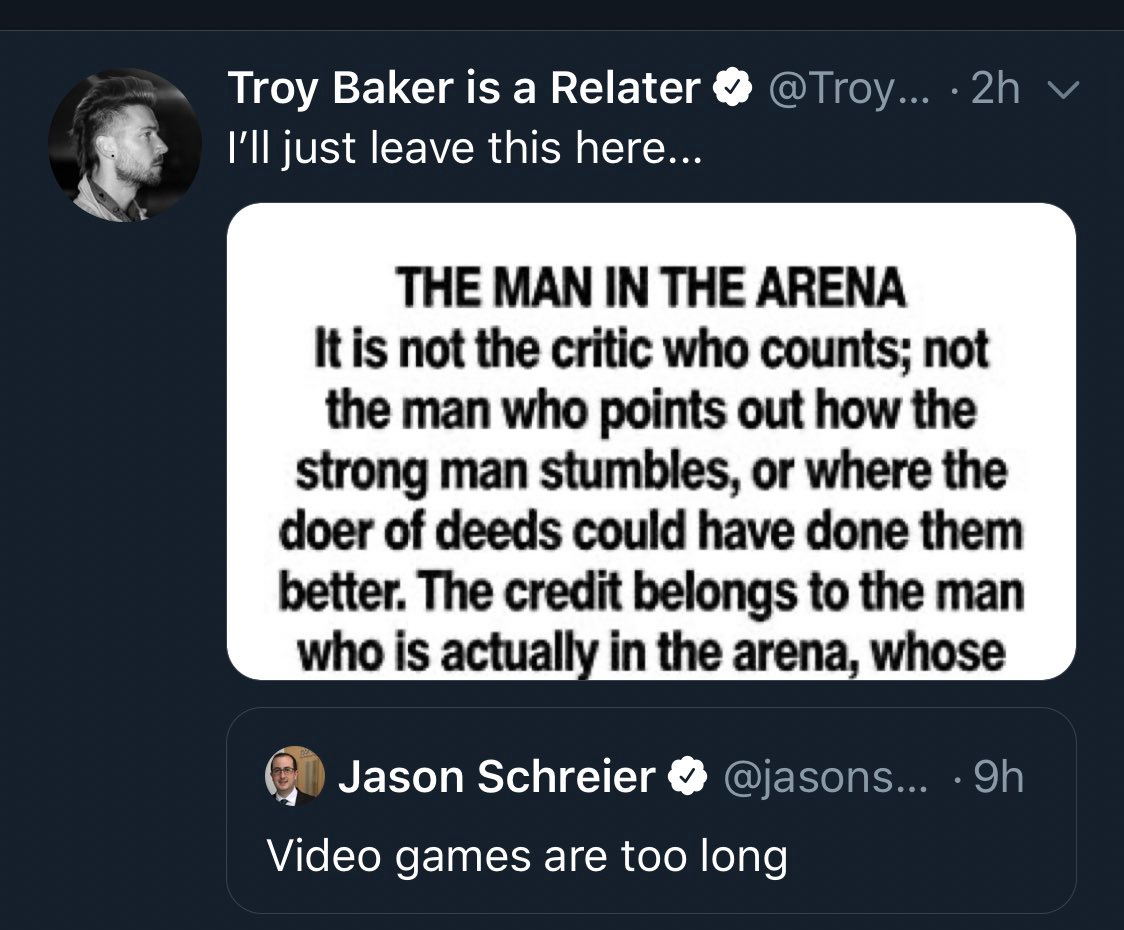

This criticism of criticism isn’t unique to music by any means. All over TikTok, you’ll see people being piled on for negative reviews of popular media. Watching a review of books on YouTube, you’ll see the reviewer spend most of the clip’s runtime begging the audience not to attack them for what they’re about to say. After some criticism of The Last of Us 2, Troy Baker (the actor who portrays Joel in the video game) tweeted a quote from Theodore Roosevelt. “It is not the critic who counts: not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles. . . . The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena . . .” Besides being extremely petty, this shows that our cultural view of criticism hasn’t made much progress in the last 120 years.

A recurring theme in attacks against criticism is the idea that the critic has no right to express their opinion because they’re not artists themselves. Just look at Lizzo’s tweet. And then there’s the idea that an artist is putting themselves out there by releasing a project and a critic is capitalizing on that vulnerability. I’d argue the person really making themselves vulnerable is the freelancer who suddenly finds themselves getting death threats because a musician didn’t like their review.

This mentality shows a complete disregard for the form. To me, there are three modes of criticism. The first is the “buyer beware” type that comes in the form of things like Goodreads reviews. These reviews are meant to inform the consumer. The second is the type that comes from people like beta readers or editors. This form of criticism is solicited by the artist from people close to them. Its purpose is to help the creator improve their project. The third type is the professional review. These pieces of criticism are a combination of the previous two. They serve to inform the consumer about a piece of art, but they also provide effective critiques of the style, form, and content of the subject. This mode serves to help other artists improve their craft as well as the piece’s creator, if they’re open to the feedback. What I’m concerned about here is this third mode.

I’m not saying that a writer must take professional criticism to heart or internalize it or even read it. If they’re open to this sort of criticism, that’s entirely up to the individual. Unlike with beta readers, they did not solicit this feedback, but it’s a necessary, inevitable part of being published; in much the same way that copy editing and cover design are.

Professional criticism is its own art form, and Andrea Long Chu’s work is an excellent representation of that. Good criticism encourages the reader to re-examine art they enjoy or dislike. It’s incisive and biting, and the prose is equally important here as it is in a novel. It helps the writer convey their thoughts in a unique, insightful manner. Good criticism is also, at times, funny.

A Little Life is a book about a queer man — Jude — and the miserable reality in which he lives. Andrea Long Chu references another review in her piece where the writer called the novel a “trauma plot” that, “uses a traumatic backstory as a shortcut to narrative.” I have a similar, but slightly different definition of the book. It’s trauma porn; an all too common theme in recent media.

To me, trauma porn is a plot that subjects its protagonist to unending tortures in order to titillate the reader. It’s lazy writing. The above quote called the trauma plot a “shortcut to narrative,” but trauma porn is a shortcut to climax. It convinces the reader to conflate tears or sadness with good story. The author subjects the reader to the torture of their protagonist for hundreds of pages and then when they close the book and find themselves depressed or tearful, they think the novel has just pulled off quite a feat by making them emote. In actuality, the practice is no more impressive than those commercials featuring a one-eyed, malnourished dog with a Sara McLachlan song playing in the background.

In her piece, Chu gives voice to my concerns and dives deep into other problems with Yanagihara’s work that I hadn’t considered. On the constant trials the author puts Jude through, Chu writes, “The first time he cuts himself, you are horrified; the 600th time, you wish he would aim.” It’s a genuinely funny line that so concisely isolates one of my biggest problems with this book.

But the criticism goes further. Chu points out that these characters Yanagihara has spent three novels tormenting all tend to be gay men. “Reading A Little Life, one can get the impression that Yanagihara is somewhere high above with a magnifying glass, burning her beautiful boys like ants,” is a line written by Chu that successfully makes me imagine the author as Sid in Toy Story, ripping the heads off gay little Ken dolls.

All of these points come together to help make Chu’s broader critique. She argues that Yanagihara is acting as some perverse protector/attacker amalgam for her protagonists. Chu writes, “The book’s omniscient narrator seems to be protecting Jude, cradling him in her cocktail-party asides and winding digressions, keeping him alive for a stunning 800 pages. This is not sadism; it is closer to Munchausen by proxy.”

This is the value of good criticism. A Little Life is a huge book — both literally and figuratively. It’s a favourite of BookTok and BookTube, and it’s a constant in the rotation of recommendations on sites like Goodreads where it has an impressive score of 4.3/5. And I hate it. I just couldn’t wrap my brain around the hype. Then Vulture published this piece and finally I had an ally. Someone agreed with me and, together, we could commiserate.

I think part of the reason for the hatred of criticism lies in our current cultural obsession with morality — especially with regard to the content of the media we consume. You don’t need to look far to find evidence of this. All over BookTok, comments sections rage with arguments about whether certain books are “problematic” and people have to defend why they do or do not enjoy a popular novel — often couching their negative reviews in language that makes it sound like their objections come from some moral standing. Suddenly, the media we like says something about our personal purity. Madison Beer had to go on an apology tour after claiming her favourite book was Lolita. On Twitter, there are hundreds of threads discussing books that are “red flags” in a potential partner. When a review is released about a piece of popular media (say, a review that criticizes an author’s portrayal of her queer characters), fans of that piece jump to smear the review lest their favourite book get relegated to the category of “problematic fav” in the public consciousness.

But that’s not the purpose of reviews or criticism. The goal is to get us to examine a piece of art from a new perspective or through a different lens — not to render our favourite pieces with a pass/fail grade regarding the morality of the content.

I don’t like this book. Maybe you do, and that’s fine. The reality is that you’re no more morally compromised for enjoying Yanagihara’s A Little Life than I am for enjoying Larson’s “Cow Tools.”

I’m grateful for good criticism. It makes me think more critically about the art that I love, and it helps me understand media that I hate. Just as often, it’s exceptional art on its own. It even gave me inspiration to write this week. Of course, people will continue to malign the form as the work of those who lack creativity or skill. My answer to that is, between Yanagihara and Chu, only one of them has a Pulitzer.

I think criticism is good when it is legitimately constructive, when the author substantiates his viewpoint. One thing that's bothered me about film criticism in the last 20 years is how it felt that most critics had stopped trying to actually prove their points, sometimes boiling down their works to 'it sucks, it sucks so much' but offering no evidence or making their critiques personal, attacking the author rather than the work.

There are things I just won't read (or watch) anymore, no matter how well done. I appreciate the critics who understand that and can send out a warning along with whatever appreciation they have for the creator's work.